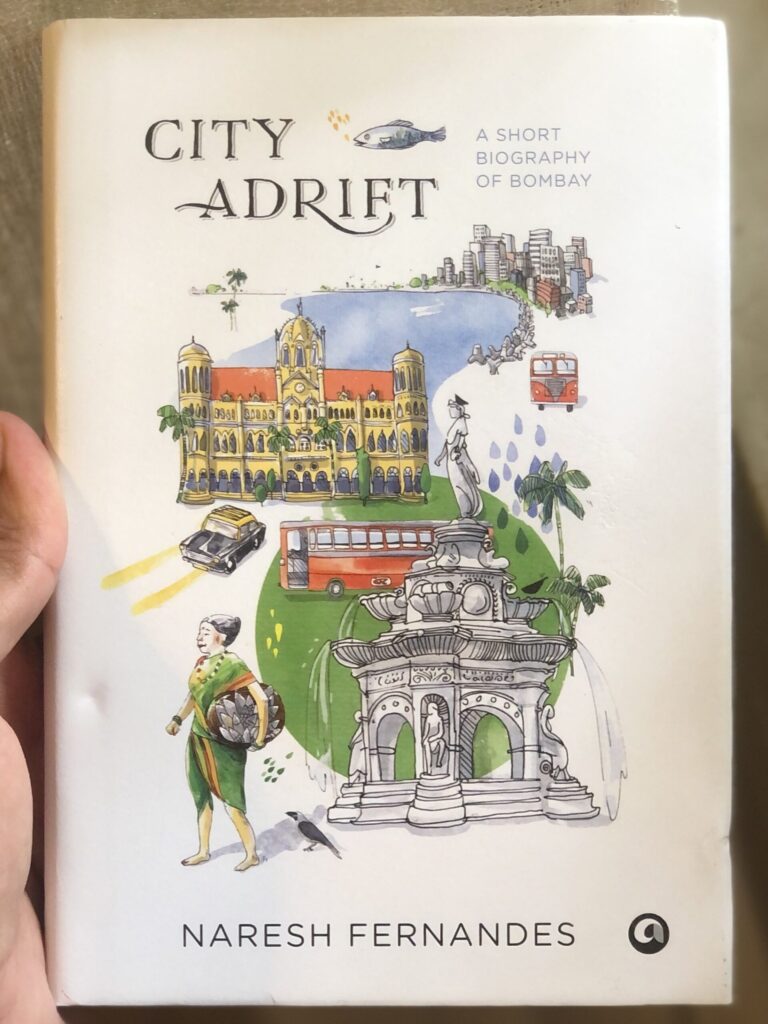

Have you ever had that feeling when you wanted to be in a place where no one would bat an eye if you had body-piercings in ten places, had a long winding dragon tattoo peeping out of your singlet, while you sang at the top of your voice sitting on the edge of the water, sipping tea, while thousands of motorists passed you by behind you? Bombay has held that special place in every Indian’s heart where no one cares how you look and the city never really sleeps (how could it? There’s more people there than the land could ever hold). Recently I had the privilege of reading a short biography of Bombay called “City Adrift”, written by Naresh Fernandes, a guy who appears to be very good at being in all the right places at the right moment. His journalistic instincts seem as good as his capacity to retain information and paint a picture with it. And that’s exactly what he does in his book; paints a very detailed picture, at least for the first half.

Naresh Fernandes, who is the editor of Scroll magazine, takes us right back to the time when Bombay was nothing but a few pieces of land separated by the raging tides of the sea, close enough for perilous travel but not that close for trade; the dowry of the Portuguese queen for the Monarch whom she would marry. The story of Bombay unfolds through the word-imagery that Fernandes weaves to tell us how the handsome part of Bombay emerged out of an attack on the forces of nature, a sort of war waged against the battling waves of the sea. As he describes interesting anecdotes that make out to be turning points in the history of the great city and its evolution, you get the jitters. The jitters that make you remember those long walks on the Worli sea-face you took on sultry evenings, hand-in-hand with that special friend, talking about the columns of the sea-link, yet to be completed, standing desolate in the waters. Those sudden Panipuri pit-stops en route to catch the 8:40 fast train. Those binge-eating walks through Mohammed Ali Road during Ramadan. Driving past crowds of people huddled at the gates of ‘Mannat’ on the way to Bandra Bandstand. Or those rides on the double-decker BEST bus from Worli Doordarshan to Crawford Market. Yes, those jitters. It’s just one of those things that makes us value what we have experienced when it connects to a long withstanding past; no matter how sordid.

Throughout the book, Naresh takes us back and forth to the beginnings and the easily foreseeable future of Bombay. One thing that struck me was how, according to Naresh, the merchant princes of present-day Bombay seem to have forgotten about their city. The fervour with which the business owners of Bombay took care of their city in the 20s through 60s seems to have waned. A more capitalistic attitude seems to have replaced the intimacy towards their city. I am easily convinced of this, since the only time we hear about the billionaires of Bombay is when their name appears on a bill that I am handed, or when it appears in a list of a leading magazine counting who has the most moolah in the world. I may be deliberately failing to mention the exceptional philanthropic activities of the rich in the city because that’s what they have become, exceptions. Also philanthropy these days seems to address communities or sections of people, rather than a city itself, not belittling the act of kindness. Before I digress, “City Adrift” is a fantastic short biography of Bombay. Although I have to stress that it is definitely short. Or maybe it is the genius of the writer to make us want more! While the first part of the book seemed like we were walking down memory lane, the second part seemed like we suddenly hauled a kaali-peeli and asked him to step on the gas and take us into the future!

The descriptions of the largest, most powerful regional political party, the Shiv Sena (I know they don’t like being called a political party; a social enterprise if you will), are somewhat hurried and at times vague. The stories of the freedom struggle and how Bombay relates to it were a refresher. Most literature about our freedom focuses on the larger cities of UP and Delhi. Here in Mumbai we only focus on the money. After all, it is the commercial capital of India. What I felt was missing are the fantastical stories of the underworld and the equally fascinating police force during the 80s, which Fernandes just lightly touches upon and leaves us with just a taste. Maybe the author wants to say, if you want the Mafia of Bombay, go read Zaidi.

Being an architect, a fervent observer, and an on-and-off resident of Bombay since 1990, I could relate to the explosive migration of people to the city and the issues of actually living in Bombay. Not only is it expensive, (we live in an apartment on the fringes of the city; a place called Kandivali), it is also the weirdest experience of life. You live in one of the safest cities in the country and yet fortify yourself in an apartment complex with a thousand security guards, CCTV, Video door phones, double security doors, and recently an app on which guests need to register themselves before entering the building. And yet, the food delivery guy arrives unannounced while I always get stopped by the security guard at the gate! One of the other experiences that suddenly popped out of my memory, when the book talked about the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the subsequent riots in Bombay, was one of my childhood visits to Fantasy Land (long gone) in Jogeshwari. I must’ve been about six. We had decided to celebrate New Year’s Eve at Fantasy Land and on our way back, our entire family was suddenly jolted into the beginnings of the riots. Halted and asked about our faiths, we escaped with narrow margins and a lost motorcycle of my uncle. One of the most harrowing experiences; a memory of the trauma that was blocked by my subconscious. Every time I read about that time in any book or watch the movie ‘Bombay’, I get reminded of how our Karma, most likely, saved our lives.

“City Adrift” is an excellent companion to your thoughts and ideas about Bombay; its past and its future. It asks, where is this city headed? As Charles Correa had mentioned, it is a “Great City, Terrible Place”, Naresh tries to make you see why and also points towards further decay that may be coming. In all fairness, it has been eight years since the book was published and many things have changed in Bombay. Notably the leadership. The Shiv Sena has finally accepted that it is in fact a political party and has taken control of its most beloved city. News of frequent flooding has been reciprocated with the building of underground storage tanks to relieve the overworked drainage systems. The Pandemic seems to have brought businesses to a realisation, after BKC laying empty for over 5 months, that the location does not matter for doing business. Navi Mumbai has seen a spurt of developmental activity and the revival of the almost-forgotten NMIA!

What would interest me is another volume of the drifting city, an addition to the story of Bombay bringing us up to date with the current scenario and what lies ahead in purview of the recent changes considered. The policies, the bureaucracy, and their whims have always influenced the built fabric of the city and its planning. We are no strangers to housing projects of Bombay that seek to exploit every loophole in the book and create one where there isn’t. We have all extended our windows and dry balconies, have we not? The excitement of this book is in its details, its anecdotes, and in its author’s calculated, journalistic ability to invoke feelings towards this giant of a city that we all have once in our lifetimes, experienced.

An unlikely abrupt end to a book review: Bombay has about 1.1 square metres of open space for every resident, that includes pavements and traffic islands. London has 31.6 square metres. These figures are from 2011. And the misunderstood ‘spirit of Bombay’ lives on.